Introduction

The Oregon Trail was much more than a pathway to the state of Oregon; it was the only practical corridor to the entire western United States. The places we now know as Washington, Oregon, California, Nevada, Idaho and Utah would probably not be a part of the United States today were it not for the Oregon Trail. That's because the Trail was the only feasible way for settlers to get across the mountains.

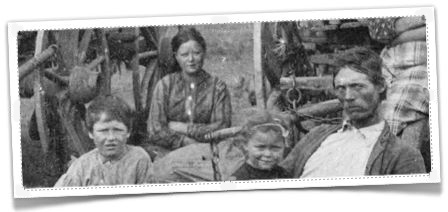

The journey west on the Oregon Trail was exceptionally difficult by today's standards. One in 10 died along the way; many walked the entire two-thousand miles barefoot. The common misperception is that Native Americans were the emigrant's biggest problem en route. Quite the contrary, most native tribes were quite helpful to the emigrants. The real enemies of the pioneers were cholera, poor sanitation and--surprisingly--accidental gunshots.

The first emigrants to go to Oregon in a covered wagon were Marcus and Narcissa Whitman (and Henry and Eliza Spalding) who made the trip in 1836. But the big wave of western migration did not start until 1843, when about a thousand pioneers made the journey.

That 1843 wagon train, dubbed "the great migration" kicked off a massive move west on the Oregon Trail. Over the next 25 years more than a half million people went west on the Trail. Some went all the way to Oregon's Willamette Valley in search of farmland--many more split off for California in search of gold. The glory years of the Oregon Trail finally ended in 1869, when the transcontinental railroad was completed.

Actual wagon ruts from the Oregon Trail still exist today in many parts of the American West; and many groups are working hard to preserve this national historic treasure.